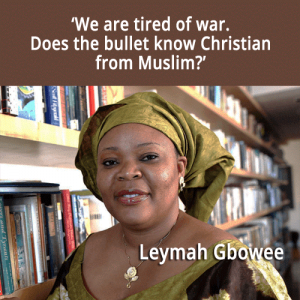

Leymah Gbowee – Alternative Christian Model For Nonviolent Jihad

Leymah Gbowee was born in Monrovia, Liberia in 1972. Leymah attended private school, served in the student council and dreamed of being a doctor. In 1989 The First Liberian Civil War broke out, throwing the country into chaos, and shattering her dreams. Thousands of people were killed and many women were violated. So Leymah fled with her mother and sisters on a boat to Ghana. Leymah says she almost starved to death in the refugee camp, and so, in spite of the risks, she decided to return to Liberia.

‘As the war subsided’ Leymah Gbowee says, ‘I learned about a program run by UNICEF training people to be social workers who would then counsel those traumatized by war’.[i] This course helped Leymah make a link between the violence she had suffered in her own home in a series of abusive relationships and the violence other women suffered in the war at the hands of both the government and guerilla militias – and out of this sense of solidarity Leymah’s struggle for peace and justice was born.

In 1998, Leymah Gbowee enrolled in an Associate of Arts degree and volunteered with the Trauma Healing and Reconciliation Program (THRP), a program operating out of St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in Monrovia that she had attended as a teenager and that had been active in peace efforts ever since the civil war started. To begin with Leymah was assigned the task of trying to rehabilitate former child soldiers.

In 1999 The Second Liberian Civil War broke out, throwing the country into chaos, and faced with another ‘boys’ war Leymah Gbowee realised ‘if any changes were to be made in society it had to be by the mothers’. [ii]

Her supervisor in the Trauma Healing and Reconciliation Program, whom she calls ‘BB’, encouraged Leymah to study peacebuilding, starting with John Howard Yoder’s The Politics of Jesus, the works of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King ‘and the Ethiopian author and conflict and reconciliation expert Hizkias Assefa.’[iii] BB also introduced her to the West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP). [iv]

‘WANEP was actively seeking to involve women in its work and I was invited to a conference in Ghana,’ wrote Leymah Gbowee.[v] Through WANEP, Leymah met Thelma Ekiyor of Nigeria, who was ‘well educated, a lawyer who specialized in alternative dispute resolution.’[vi] Thelma told Leymah of her idea to start a women’s organization. ‘Thelma was a thinker, a visionary, like BB. But she was a woman, like me.’[vii]

Within a year Thelma had managed to get the funding from WANEP to set up the Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET) and Leymah Gbowee had taken on the unpaid position of the WIPNET leader in Liberia.

In 2002, with her five children, ‘now including an adopted daughter named Lucia “Malou”, living in Ghana under her sister’s care’,[viii] Leymah Gbowee was spending her days working on trauma-healing and her evenings working on peace-building. ‘Falling asleep in the WIPNET office one night, she (had) a dream where she says God had told her, “Gather the women and pray for peace!”[ix]

Leymah Gbowee believed the voice she heard was from God but didn’t believe she was the job was for her. ‘She didn’t feel worthy. After all, she was living with a man who was married to another woman. “If God was going to speak to someone in Liberia, it wouldn’t be to me!” she thought. Some friends helped her to understand that the task was not meant for others, as she thought; but for her to act upon it herself’.[x]

So Leymah Gbowee ran a training session and began organizing a peace prayer campaign. Because the war was being fought between a so-called ‘Christian’ President and a so-called ‘Muslim’ opposition, Leymah, a Christian, intentionally collaborated with Asatu, a Muslim woman. They started “going to the mosques on Friday at noon after prayers, to the markets on Saturday morning, to two churches every Sunday.”[xi]

Working across religious lines, (‘Does the bullet know Christian from Muslim?’) [xii] the Women of Liberia Mass Action For Peace ‘started with a few local women praying and singing in a fish market’[xiii] and eventually became a mass movement of thousands of Christian and Muslim women gathering in Monrovia for months. ‘They prayed for peace, using Muslim and Christian prayers, and held daily nonviolent demonstrations and sit-ins in defiance of orders from the tyrannical president at that time, Charles Taylor’. [xiv]

To make themselves more recognizable, ‘all of the women wore T-shirts that were white, signifying peace, and white hair ties’.[xv] They handed out flyers, which read: “We are tired! We are tired of our children being killed! We are tired of being raped! Women, wake up – you have a voice in the peace process!” They ‘also handed out simple drawings explaining their purpose to the many women who couldn’t read’.[xvi]

They staged protests, which included the threat of a sex strike – saying that as many of them as they could would refuse to have sex with their partners until they stopped fighting, laid down their weapons and made peace. Leymah Gbowee says, “The [sex] strike lasted, on and off, for a few months. It had little or no practical effect, but it was extremely valuable in getting us media attention” for our campaign.[xvii]

On April 23, 2003, Taylor finally granted the women a hearing. ‘With more than 2,000 women amassed outside his executive mansion’, Leymah Gbowee was the person designated to speak for them. She said: We are tired of war. We are tired of running. We are tired of begging for bulgur wheat. We are tired of our children being raped. We are now taking this stand, to secure the future of our children. Because we believe, as custodians of society, tomorrow our children will ask us, “Mama, what was your role during the crisis?” [xviii]

Their role that day was to pressure the President into promising to attend peace talks in Ghana to negotiate with the LURD and MODEL rebel groups who were fighting against his government. And they succeeded.

But the peace talks in Ghana dragged on through June and July without any progress, while the killing, looting and raping continued unabated in Liberia. So Leymah Gbowee led a group of hundreds of Liberian women (many of them refugees in Ghana) to hold a sit-in at the hotel where the talks were being held, holding signs screaming silently: “Butchers and murderers of the Liberian people – STOP!”[xix]

The women said they would stay sitting in the hallway, holding the delegates “hostage” until a peace agreement was reached. ’General Abubakar (a former president of Nigeria) who proved to be sympathetic to the women, announced with some amusement: “The peace hall has been seized by General Leymah and her troops.” When the men tried to leave the hall, Leymah and her allies threatened to rip their clothes off: “In Africa, it’s a terrible curse to see a married or elderly woman deliberately bare herself.” With Abubakar’s support, the women remained sitting outside the negotiating room during the following days, ensuring that the “atmosphere at the peace talks changed from circuslike to somber.”[xx]

The Liberian war ended officially weeks later, with the signing of the Accra Comprehensive Peace Agreement on August 18, 2003.[xxi] “But what we [women] did marked the beginning of the end.”[xxii] As part of the peace agreement the President, Charles Taylor, was sent into exile. And, as a result of the women’s movement, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf was inaugurated as the first elected woman President in Africa.

In 2011 Leymah Gbowee and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize (with Tawakei Karmen) “for their nonviolent struggle for the safety of women and for women’s rights to full participation in peace-building work.”[xxiii]

Leymah Gbowee ‘has continued her work in peace and conflict resolution, and is now leading the Liberia Reconciliation Initiative, one of the six coordinating organizations that created and guides the roadmap of resolution. She is the President of the Gbowee Peace Foundation Africa, based in Monrovia, and also serves as the Executive Director of Women, Peace and Security Network Africa (WIPSEN-Africa)’[xxiv]

All of us who would engage in Strong-But-Gentle Struggle For Justice Against Injustice would do well to gather a group of friends, watch a DVD of the brilliant documentary Pray The Devil Back To Hell, about Leymah Gbowee and the interfaith women’s peace movement in Liberia, and discuss what we can learn from their story for our struggle.

Dave Andrews p140-4 The Jihad Of Jesus http://bit.ly/1CedNDX

[i] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 50

[ii] “2009 Gruber Foundation Women’s Rights Prize”. Gruberprizes.org.

[iii] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 88

[iv] “WANEP,” http://www.wanep.org/wanep/about-us-our-story/about-us.html.

[v] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 101

[vi] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 107-108

[vii] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 109.

[viii] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 148.

[ix] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 122

[x] http://www.guideposts.org/blogs/journey/leymah-gbowee-and-hard-work-faith

[xi] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 126.

[xii] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 129.

[xiii] “2009 Peace warrior for Liberia”. Odemagazine.com. 2009-07-20

[xiv] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 128 and p. 135.

[xv] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 136.

[xvi] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 127.

[xvii] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 147.

[xviii] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 140-1.

[xix] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 161.

[xx] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 161-2

[xxi] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 164.

[xxii] Leymah Gbowee, Mighty Be Our Powers (New York: Beast Books, 2011), written with Carol Mithers, p. 163.

[xxiii] “The Nobel Peace Prize 2011 – Press Release”. Nobelprize.org.

[xxiv] http://www.peacejam.org/laureates/Leymah-Gbowee-13.aspx